Take a Deep Dive into the Science of Reading

Join Waterford’s Science of Reading virtual summit to explore how the brain learns to read and get Strategies for effective, research-based instruction from literacy expert and Vice President of Curriculum Julie Christensen.

Plus, find a variety of upcoming and on-demand video series led by early education experts through the Webinar Library, featuring topics chosen with administrators in mind, like:

- Impactful Family Engagement Made Easy

- Understanding the Six Instructional Strands for Literacy

- Improving Student Outcomes with Professional Services

Teaching students to read is so much more than sitting them down in front of a book. It takes an intentional mix of explicit classroom lessons, individualized support, and family engagement to help children develop strong reading skills. But, how do we know what strategies will work best? Have you ever stopped to think about what brain science says about how children learn to read—and how that might make your teaching even more effective?

Staying up-to-date on the research behind how children learn to read can help you make informed decisions about classroom instruction. Educational research offers valuable insights about the neuroscience of reading and how educators can teach literacy more effectively.

What is the Science of Reading?

What exactly is the science of reading, and how can it inform classroom instruction? In a presentation with Waterford.org, Julie Christiansen reaffirmed that the science of reading is “the body of research from neuroscience and education that helps us understand how the brain learns to read and how to deliver instruction that helps students learn to read most effectively.”[1]

What exactly is the science of reading, and how can it inform classroom instruction? In a presentation with Waterford.org, Julie Christiansen reaffirmed that the science of reading is “the body of research from neuroscience and education that helps us understand how the brain learns to read and how to deliver instruction that helps students learn to read most effectively.”[1]

The science of reading is not, she says, “a new idea, a passing fad, a preferred viewpoint, or a program.” Instead, the science of reading points to key learning principles and clear building blocks for literacy. These ideas can shape the way your teachers plan instruction.

Why the Science of Reading Matters

Most children naturally learn to talk through exposure to spoken language. However, the same is not true for learning to read. Julie Christensen, Ed.M, notes that, “by contrast, learning to read requires several years of intentional instruction.”[1]

How educators teach during a student’s early years of reading instruction matters for the child’s lifelong academic success. Your teachers can play a key role in giving students a strong start by staying current on literacy development research and using these findings to inform instruction.

How Do Children Learn to Read?

The brain’s reading network is formed in the left hemisphere. Specific areas of the brain process visual information and letter sounds. Other areas of the brain help us retrieve the meanings and pronunciations of words. In non-readers and developing readers, these areas of the brain are not yet connected. The process of learning to read literally changes the brain, forming neural pathways between the areas that must work together to make reading possible.

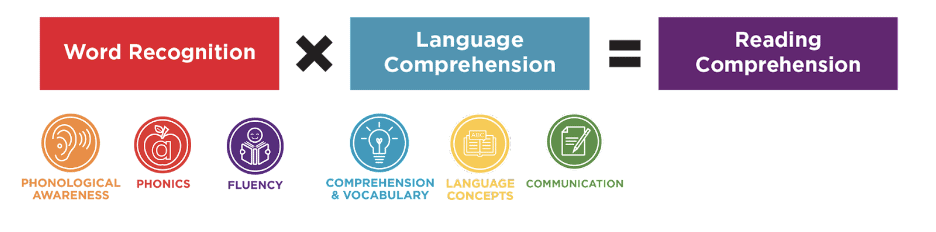

Two instructional frameworks are helpful in understanding the science of reading. The Simple View of Reading (below) states that proficient reading comprehension is the product of word recognition skills and language comprehension skills.

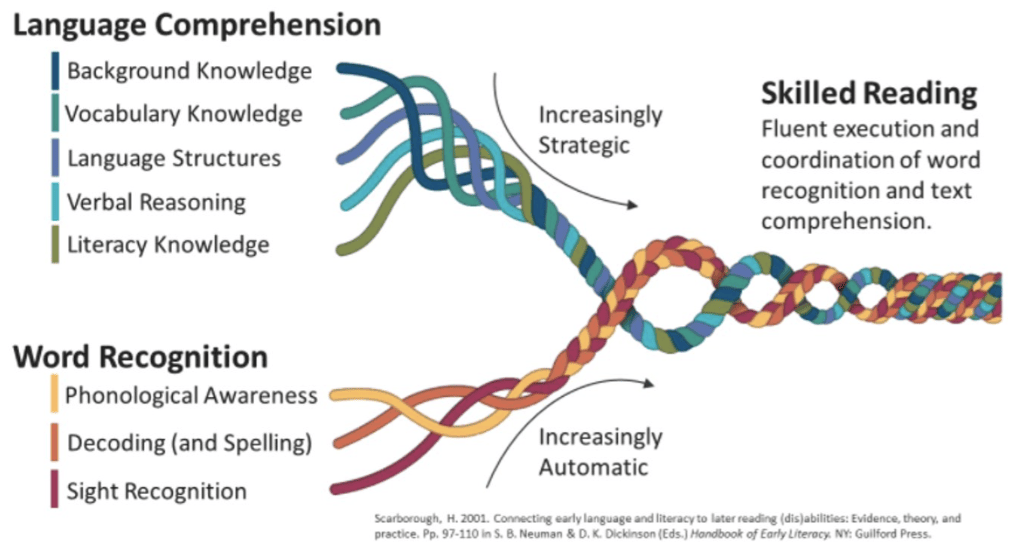

Scarborough’s Reading Rope (below) expands on the Simple View by outlining sub-areas within both word recognition and language comprehension.[2] Word recognition, for example, pinpoints phonological awareness, decoding and spelling, and sight recognition as important stepping stones. Language comprehension expands in the Reading Rope model to include background knowledge, vocabulary knowledge, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge. These skills are woven together to help a student read automatically and strategically.

A systematic and intentional curriculum for teaching reading will use instructional strands that align with the word recognition and language comprehension elements in the above reading frameworks. For example, Waterford’s curriculum is designed around the following strands:

- Phonological Awareness

- Phonics

- Reading Fluency

- Reading Comprehension and Vocabulary

- Language Concepts

- Communication

These strands are aligned with the Simple View of Reading and with the essential components of reading as identified by the National Reading Panel.[1] Together, they are the key puzzle pieces for literacy development.

Understanding the science of reading helps us see clearly how to foster skill development for students who are learning to read. Frameworks such as Scarborough’s Reading Rope, which illustrates how skills are woven together to produce reading proficiency, point to instructional approaches that align with the way the brain’s reading network operates.

How to Use the Science of Reading in the Classroom

Now that we’ve hit on a few key ideas around the value of the science of reading, let’s discuss how you and educators in your district can stay informed and use that knowledge in your curriculum. Waterford’s Foundations of the Science of Reading virtual summit begins October 18th. Register here to learn how the latest research can guide literacy strategies on a classroom, school, and district level.

Books on literacy development are an accessible way to learn more. Make sure that these books are recommended by experts in the field.

Waterford.org recommends the following books for in-depth study:

- Speech to Print: Language Essentials for Teachers by Louisa Moats

- Essentials of Assessing, Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties by David A. Kilpatrick

- Reading in the Brain by Stanislas Dehaene

Additionally, search for professional development opportunities on the science of reading (like Waterford’s Science of Reading virtual summit) including presentations, self-paced courses, or podcasts. This can be a great way to learn the latest strategies from today’s educational researchers in a way that fits your schedule as a busy educator.

Finally, collaborate with other educators. Studying reading science by yourself can be overwhelming. Together, however, you can share what you’ve learned and brainstorm ways to put that knowledge to use. You can start a book club based on one of the recommended titles shared above. Or you can implement a school or classroom strategy together and discuss your progress at a follow-up meeting.

Read Waterford’s full Science of Reading article series and learn how to support your teachers with research-driven strategies as they plan for classroom instruction. Continue learning with the next three articles:

Sources:

1. Christensen, J., Persch, K., & Esser, L. “An Overview of the Science of Reading.”Video from Waterford.org. Nov. 2021.

2. Christensen, J. “The Science of Reading: From Research to Instruction.” Waterford.org, April 2022.

Further reading:

Gough, P., & Tunmer, W. (1986). “Decoding, reading, and reading disability.” Remedial and Special Education, 7, 6–10.

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). “Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice.” In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy. New York: Guilford Press.